Art & Architecture

Forged in the enduring spirit of reverence, adoration and gratitude, the Mandir is a humble tribute to the inexpressible majesty and unbounded glory of the Divine. As a result, the Mandir is both a labour of love and a work of art.

Externally and internally, structural features such as columns and beams are profusely carved with traditional Hindu motifs of auspiciousness, peace and piety. It is where architecture becomes art and art becomes architecture, and both become devotional.

Exterior

Atop the main marble staircase, the roopchoki (or ornate front porch) is a traditional entrance leading into the Mandir. Delicate dancing figures around the columns and serving as struts (angled supports) welcome visitors with gifts of flowers, incense and music.

Along the outside, the creamy white Bulgarian limestone is worked into a frieze (intricate wall) of patterned carvings intermittently embellished with figures of divinities and featuring decorated windows and balconies.

Above, the large fluted central dome and its accompanying cupolas (smaller domes) rise serenely from the roof.

Behind them are the shikhars, or spires, each an intricate set of sculpted towers soaring above the shrines directly beneath them.

Each spire is crowned by the kalash, a set of gilded urns of descending size symbolising the completion of the mandir.

Beside them rise the flag masts; the fluttering red-and-white flags serving as notice that the sovereign Deity is in residence. The Mandir is the House of God.

Interior

Inside on the upper floor, the maha-mandap (‘Great Hall’, or nave) is a milky-white sanctuary of Carrara and Ambaji marble covered with a froth of carvings.

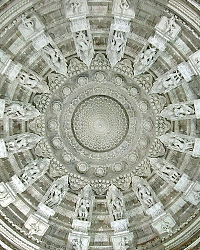

At its heart is the segmental cantilevered dome rising 10 metres (30 feet) high and stretching 8.5 metres (28 feet) across, brimming with tender floral motifs. From its centre, the two-and-a-half tonne keystone descends like a stone chandelier. Encircling it, figures of celestial beings beam down showering their blessings and benedictions.

The dome rests on an octagonal bay surrounded by windows allowing natural light to seep in through the stone latticework.

Supporting the ensuing structure is a forest of intricately sculpted columns (or ‘pillars’). From their base to their capitals (‘heads’), each one is embellished with delicate figures and themes from Hindu lore. Other columns in the upper sanctum feature natural and geometric motifs.

Between the columns, undulating open arches reach across in a continuous stream. Along the outer aisles, they form an arcade of arches stretching to the back of the sanctum.

Above, the ceiling is replete with deep floral and geometric patterns, each section unique in design to any other in the maha-mandap.

At the far side and around the outer wall in recesses lie the garbh-gruh, the sanctum sanctorum wherein the sacred images of the Deities are enshrined in gilded, throne-like canopies called sinhasans.

Built according to ancient Hindu texts yet satisfying modern British building regulations, the mandir also incorporates features such as under-floor heating, a lift for the infirm and disabled, and two (marble staircase) fire exits.

To view a 360° panoramic view of the inner sanctum, please click here. (Courtesy of the award-winning photographer Mark Pain.)

“It is impossible to stand inside here without feeling spiritually moved and inwardly contemplative.”

Time Out City Guides

Overview

-

- 7 shikhars (spires)

- 6 ghummats (domes)

- 193 sthambhas (columns)

- 32 gavakshas (windows)

- 4 jharukhas (balconies)

- 500 different designs

- 55 different ceiling designs

- 26,300 carved stone pieces

- Height: 21 metres (70 feet)

- Width: 22.5 metres (75 feet)

- Length: 60 metres (195 feet)

Inside on the upper floor, the Maha-Mandap[PTD1] (‘Great Hall’, or nave) is a milky white sanctuary of Carrara and Ambaji marble covered with a froth of carvings.

At its heart is the segmental cantilevered dome rising 10 metres (30 feet) high and stretching 8.5 metres (28 feet) across, brimming with tender floral motifs. From its centre, the two-and-a-half tonne keystone drips downwards like a stone chandelier. Encircling it, figures of celestial beings beam down showering their blessings and benedictions.

The dome rests on an octagonal bay surrounded by clerestory windows allowing natural light to seep in through the stone latticework.

Supporting the ensuing entablature is a forest of intricately sculpted columns. From their base to their capitals and corbels, each one is embellished with delicate figures and themes from Hindu lore. Other columns in the chamber feature natural and geometric motifs.

Between the columns, undulating arches with open spandrels reach across in a serpentine stream. Along the outer aisles, they form an arcade of arches stretching to the back of the hall.

Above, the ceiling is replete with deep floral and geometric patterns, each section unique in design to any other in the maha-mandap.

At the far side and around the outer wall in recesses lie the garbh-gruh, the sanctum sanctorum wherein the sacred images of the Deities are enshrined in gilded, throne-like canopies called sinhasans.

Built according to ancient Hindu texts yet satisfying modern British building regulations, the mandir also incorporates features such as under-floor heating, a lift for the infirm and disabled, and two (marble staircase) fire exits.

[PTD1] [PTD1]I propose we begin to call this area by its technical name – either Mandap or Maha Mandap, translated as the great chamber or great hall. (Many old and state buildings have a ‘Great Hall’ for public functions, etc. so seems appropriate.) This is to avoid confusion with the Mandir (the whole building) and its upper floor.

For an English term that we will need to use now and again, there is either “sanctum” (or “upper sanctum” sometimes to indicate the upper floor) or “sanctuary”. In Church parlance, a sanctuary is the area surrounding the altar (what relates to our khands). And “sanctum” still means holy place. (They are essentially the same word in Latin & English.)

The ‘sanctum sanctorum’ or ‘inner sanctum’ is more properly the garbh-gruh, where no one is allowed in – the ‘innermost chamber’, ‘the holiest of holies’, ‘a place of inviolable privacy’.

So ‘(upper) sanctum’ and ‘sanctum sanctorum’ – yes?