Murti Puja: Image Worship in Hinduism

Murti puja is the key Hindu practice of worshipping sacred images of God and divine personalities. It helps Hindus to establish, express and enhance their relationship with these divinities.

Murti puja is the key Hindu practice of worshipping sacred images of God and divine personalities. It helps Hindus to establish, express and enhance their relationship with these divinities.

A murti becomes venerable for Hindus only after it is enlivened with the spiritual energy and essence of the Deity. Because it contains the living presence of the Deity, a murti is more than a physical representation or a meditational tool. And so devout Hindus can see beyond the stone or metal or paint, and endeavour to relate to and serve the divine spirit within.

Hindus believe that God pervades everything and so he already has a presence in all beings and objects. However, when an image prepared according to scriptural prescriptions is ritually infused by a spiritual authority, such a murti becomes especially worthy of and conducive to worship.

Origin

The practice of murti puja can be traced to Vedic times, when ancient rishis (seers) created symbols and images of the divinities they revered and wanted to thank. These included the deities presiding over forces of nature, such as Varuna (sea), Indra (rain), Surya (sun), Vayu (wind), and others. With mantras and elaborate rituals, the rishis then invoked each deity into the images so that the stone, wooden, clay or metallic statue would become a murti – a focus of veneration.

For example, the Rig Veda – the oldest text known to humans – mentions expert murti-sculptors such as Tvashta (1.20.6), and vividly describes the forms of sacred images of various deities (8.29). Other Vedas and later texts similarly attest to a longstanding tradition of murti puja in Hinduism.

Design and Crafting of Murtis

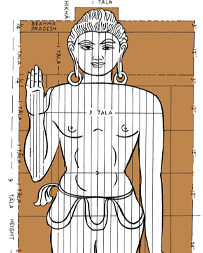

Underlying the sacred images seen in mandirs is the exact discipline of Hindu iconography. The Shilpa Shastras – or canonical manuals of Hindu religious art – meticulously describe the precise shape, posture, gestures, dimensions, material, and process of sculpting a murti. To ensure and preserve the correct ways, a plethora of technical terms, implements and instructions were developed for the experts.

For example, exact anatomical features and proportions are ensured by an intricate system of measurements. Each unit is called a ‘tāla’ – literally ‘beat’, carried over from the rhythmic measures of classical Indian music and dance. This is used to determine the finest of details, from the length of a fingernail to the curvature in an eyebrow. A basic overview is provided in the figure below:

Liturgical treatises, such as the ancient Panchratra Samhitas, also explain the metaphysical significance of each stage of manufacture and prescribe specific mantras to sanctify the process, including rites for the implements used by the sculptors.

In addition, the sculptors themselves have to undergo several purifactory rites and certain yogic practices to render them spiritually suitable and artistically endowed to create the images. It is said that these artists enter into moods of deep yogic meditation, thus fashioning images not out of fanciful imagination but in accordance with scriptural canon.

Materials: Sacred images are usually made from stone or metal, or are paintings. For example, most of the murtis at BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir, London are made from marble, except Harikrishna Maharaj, which is made of panch-dhatu – a mixture of five pure metals: gold, silver, copper, iron and lead. A painting of the gurus can also be seen between the central and left shrines.

An ancient Hindu text, the Shrimad Bhagavat Puran [11.27.12], lists eight types of materials from which sacred images can be made: shaili (stone); lauhi (metal); darumayi (wood); lepya (clay or sandalwood paste); saikati (sand); lekhya (ink, paint or etchings); manimayi (gems), and manomayi (mental visualisations).

Hand Gestures: Gestures (or mudras) are important in Hindu art, especially hand gestures. They help reveal the ‘characteristics’ of each Deity. In the central shrine, for example, the left hand of Bhagwan Swaminarayan is a raised palm. This is called the abhay-mudra, signifying his granting of fearlessness to all devotees because he is the forgiving guardian. The left hand of Gunatitanand Swami has the palm raised with the index finger and thumb touching. This is called the gnan-mudra, revealing him as the conferrer of true spiritual knowledge. And Gopalanand Swami‘s left hand is held out facing upward, in the sevak-mudra, symbolising the unflinching humble service to God of a liberated soul. (More about the theology behind these murtis can be learnt here.)

Invocation Ceremony

What sets apart murtis from other statues or paintings of Deities is the invocation ceremony, or pran-pratishtha vidhi. This is the culminating ceremony in an elaborate set of rituals which begin with various purifactory rites to prepare the images, shrines and entire mandir for the presence of God. After various other rituals, this concluding ceremony involves invoking each part of the Deity into the corresponding part of the image, before finally, the pran – life-source – is also invoked, transforming the image into a murti with the living presence of the Deity.

Most importantly, the pran-pratishtha ceremony must be performed by a brahmaswarup guru – an enlightened being in whom God fully resides and through whom he works. As the Vaihayasi Samhita (9.82-84 & 9.90) of the Panchratra tradition stipulates: In whose every limb and organ fully resides God, only that pure guru is eligible to perform the pran-pratishtha ceremony, for it is only such a great soul who can invoke the Supreme within his heart to enter the murti.

So just as a piece of stone becomes a statue at the hands of an expert sculptor, at the hands of an enlightened guru, the statue is transformed into a sacred image of God.

Types of Murtis

There are three basic types of murtis prevalent within the bhakti traditions of Hinduism, and all three can be found at the Mandir.

1. Sthavar (‘immovable’): These are the large, stone and metallic murtis enshrined in the upper sanctum of the Mandir.

2. Jangam (‘movable’): In addition to the various large murtis, two smaller metallic murtis are also served in the Mandir. They are movable, and when not in arti, are normally placed in the Sukh Shayya altar, between the central and right shrines. These murtis also grace festivals and celebrations, sometimes outside of the Mandir as well.

3. Utsav (‘festival’): The murtis presiding over various parts of the assembly hall in the Haveli and elsewhere are called utsav murtis. They are not attended to in the same manner as other murtis, but nevertheless provide an important presence during assemblies and festivals.

Attending to the Deity

The living presence of the Deities in each sacred image means that they are devoutly served like real living persons throughout the day.

This begins in the early morning, when the Deities are gently awakened (at 5.15am), and continues through to when they retire for rest (at 9.00pm).

An important aspect of attending to the Deities is the offering of various meals throughout the day, called thal. This includes three main meals – breakfast at 6.30am, lunch at 11.00am, and dinner at around 7.30pm – and a platter of fresh and dry fruits as well as fresh fruit juice at around 3.30pm.

Many of these timings also relate to the five artis performed during the day: Mangala Arti at 6.00am, Shangar Arti at 7.30am, Rajbhog Arti at 11.45am, Sandhya Arti at 7.00pm, and Shayan Arti at 8.00pm.

Vachanamrut Gadhada I-68[/quoteLineRef]"

Between the first and second artis, the Deities are dressed and adorned. This is another important part of attending to the murtis, called shangar, and involves an assortment of garments, adornments, garlands and flowers.

A team of sadhus (Hindu monks) and pujaris (priests) thus attend to the Deities throughout the day. And while it is an art mastered after special training and much practice, it demands, above all, the devotion and appreciation of the living presence of God within the images.